By Galo S Mirth

Millennium Castle (Japanese: ミレニアム囲い, Millennium-gakoi) is one of the most distinctive king shelters in modern shogi. It first became widely recognized around the year 2000 as an idea for the Static Rook (居飛車) side when facing Ranging Rook (振り飛車), and it is also known by several nicknames, including Miura Castle (三浦囲い) and Tōchika (トーチカ), “pillbox” or “bunker.”

What makes Millennium Castle especially interesting is that it does not try to be the hardest fortress possible. Instead, it tries to be hard enough while accomplishing three strategic goals:

- Move the king off a dangerous bishop diagonal.

- Keep key defending pieces connected so the position is resilient.

- Leave the left knight available for attack in many variations.

This article explains what the castle looks like, how it entered top-level play, and the core theories that make it useful.

What Millennium Castle Looks Like (Typical Shapes)

Millennium Castle is easiest to recognize by the king’s unusual placement: the king often sits on the left knight’s starting file (for Black, this is typically around 8-9 file territory), then gets surrounded by three (sometimes four) generals (gold and silver) plus the edge pieces.

Japanese sources often distinguish two common “families” of Millennium depending on whether the structure is built around a 6-6 bishop (for Black) or a 6-7 gold (for Black). In practice, these names refer to the shape you see in the defensive wall.

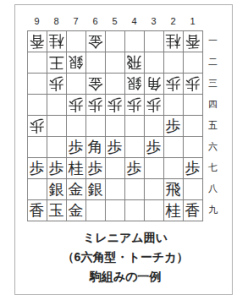

A) The “6-6 bishop type” (often called Tōchika)

In one representative form, Black’s bishop comes to 6-6 and the left knight jumps to 7-7, after which the king tucks deep to 8-9. The wall of golds and silvers forms a compact, rounded barrier in front of the king, resembling a pillbox.

Key visual cues:

- The king is deep (often 8-9).

- The “roof” is supported by generals and a bishop that can help both defense and counterplay.

- The king is not sitting on the same long bishop diagonal that so often haunts more standard castles.

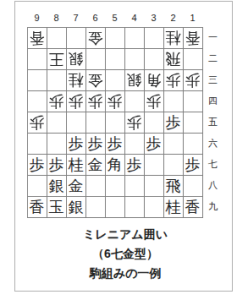

B) The “6-7 gold type”

Another common family uses a gold on 6-7 to strengthen the upper side and coordinate the defenders. This type is sometimes described as being built with an eye toward upper-side stability and flexibility.

Key visual cues:

- A gold placed on 6-7 helps create a durable roof.

- The defenders remain connected, which can matter a lot once the game turns tactical.

A note about notation and “mirroring”

Like many castles, Millennium is often shown in Japanese sources with coordinates from one side’s perspective, and you will also see mirrored diagrams (Black and White, or left and right). The essential idea is consistent: the king is sheltered behind a compact wall, shifted away from the most common bishop lines, and the left-side pieces can stay available for active play.

How It Became Famous: From Idea to Professional Mainstream

Millennium Castle’s name is tied to the period when it started being played “on purpose” at the professional level around the year 2000. Japanese references describe it as becoming a recognized countermeasure in an era when certain Ranging Rook systems were highly influential.

Several points stand out in Japanese accounts:

- Hiroyuki Miura (三浦弘行) is strongly associated with popularizing it in professional games.

- It is also described as having roots in earlier usage and study, including references to Osamu Nakamura (中村修) as an origin point in some accounts.

- The structure was discussed under multiple names (Millennium, Tōchika, Miura Castle, Kamaboko, and others), reflecting the natural “naming chaos” that happens when a new idea spreads.

Millennium Castle is also linked to awards and “new idea” recognition in shogi culture. Japanese sources connect Miura’s use and refinement of this king shelter to the Masuda Kōzō Award (升田幸三賞), a prize for notable new moves or new strategic ideas.

The Core Theories That Make Millennium Useful

A fortress is not only about hardness. It is about buying time, avoiding your opponent’s most dangerous lines, and placing your pieces so that defense and offense cooperate.

Here are the most important theories Japanese sources emphasize.

1) Escaping the bishop diagonal

A recurring selling point is that the king ends up off the most direct bishop lines that frequently decide Ranging Rook positions. Compared with some other deep castles, Millennium can reduce the chance that a single bishop check or bishop sacrifice line immediately becomes decisive.

This does not mean the king is invincible. It means the most obvious “laser line” is often missing, forcing the attacker to spend extra time creating new entry points.

2) Keeping the left knight active

One widely noted difference from certain other deep fortresses is that Millennium often allows the left knight to remain an attacking resource rather than being locked into pure defense.

That matters in practical play because a knight that can jump into the fight can:

- pressure key squares,

- support a pawn break,

- and help convert defense into initiative.

This is a big part of why Millennium can feel “modern.” The castle is not only a bunker. It is part of a plan.

3) A connected wall of generals (practical resilience)

Millennium usually surrounds the king with three generals (golds and silvers), sometimes four. When these pieces are connected, it becomes harder for the attacker to win by simple tactics.

In many shogi attacks, the defender loses when one key general is dragged away, or when a single square becomes weak and cannot be covered twice. A connected structure helps reduce that kind of failure.

4) The tradeoff: not as hard as Anaguma

Japanese sources explicitly compare Millennium to Anaguma (穴熊) and treat it as somewhat less hard in absolute terms. The advantage is often about other factors: the bishop diagonal issue, practical piece coordination, and how fast you can reach a playable middlegame without allowing an easy “assembly-phase punishment.”

In short:

- Anaguma: maximum hardness, but can have its own strategic liabilities.

- Millennium: “hard enough,” with strategic benefits in certain matchups.

5) Strategic weaknesses: edge and central distance, plus upper-side pressure

No castle is free. Japanese discussions note that while Millennium can have good durability against edge attacks, the king may be less far from the center than in the deepest fortresses. Also, even though the king is deeply placed, that does not automatically mean it is unbeatable from above.

The practical takeaway is:

- Millennium is a fortress with plans, not a fortress that you can build and then ignore.

- You still must watch for upper-side breaks and central thrusts.

Typical Use-Cases in Real Play

Historically, Millennium is introduced as an anti-Ranging-Rook idea for the Static Rook side. Over time, Japanese sources also discuss the interesting modern development where even the Ranging Rook side may adopt a Millennium-like structure in certain matchups.

This evolution is important. It shows the idea is not only a single “anti-system.” It is a flexible concept: shift the king off the most direct bishop line, connect the defenders, and keep a key knight available for later play.

A Simple Mental Picture (for English-speaking learners)

If you want a fast way to remember Millennium Castle, think:

- King goes deep, near where your left knight started.

- A tight dome of golds and silvers forms in front of the king.

- Your king is not sitting on the most common bishop sniper line.

- Your left knight often stays available as an attacker.

That combination is why many players find Millennium so appealing once they see it for the first time.

Sources (Japanese)

- Japanese Wikipedia, 「ミレニアム囲い」 (overview, history notes, named variants, comparative notes).

- 日本将棋連盟コラム(一瀬浩司), 「都成五段が快調に指し回し、強敵・澤田六段に快勝したミレニアム(振り飛車)の組み方(1)【玉の囲い方 第79回】」 (examples and discussion of modern Millennium usage).

- 将棋ペンクラブブログ, 「『三浦囲い』か『トーチカ』か『かまぼこ囲い』か『ミレニアム囲い』か」 (naming history and period commentary).

- 将棋ペンクラブブログ, 「中村修九段が開発者、三浦弘行九段が開拓者のトーチカ」 (historical narrative around development and adoption).